December, 1979: Moja Joins Washoe & Loulis in Oklahoma

Adapted from Chapter 10 of Next of Kin, by Roger Fouts with Stephen Tukel Mills (pp. 248-251).

... In early December I got a phone call from Allen Gardner.

"Roger, we can't continue with Moja," he said. "We think the best solution is to send her to you."

Moja was the oldest chimp in the Gardners' second signing study. Her name means "number one" in Swahili, and she had been with the Gardners since infancy and was now seven years old. Allen and Trixie had moved out of the small house where Washoe was raised and onto a seven-acre former "divorce ranch" where people used to stay when they came to Reno for its famous "quickie" divorces. The Gardners lived in the ranch's farmhouse while each of the three chimps had their own small cabin.

They had been calling us for nearly a year, asking for advice about Moja's increasingly strange behavior. She was biting people without warning and for no apparent reason. This didn't seem all that unusual to me. I've known plenty of human toddlers who think it's their job to bite anyone and everyone. Unfortunately, some of the Gardners' project assistants were refusing to work with Moja. The others started wearing whistles to let the students working with other chimps know that Moja was about to enter their territory. After a while, when no one would work with Moja, Allen brought back Greg Gaustad, my veteran coworker from Project Washoe. But now Greg had decided to move on again...

The Gardners were beside themselves. They no longer had the power to force Moja inside. And even if they could, no one wanted to work with her. Their only avenue of escape, apparently, was to send Moja to us. In a déjà vu of Washoe's transfer to Oklahoma a decade earlier, Allen told me that he had already planned Moja's move to our facility at South Base. Greg Gaustad would bring her by airplane, and he would stay for a few days to help in the transition.

Even after ten years, saying no to Allen Gardner was unthinkable to me. So Debbi and I agreed to take on Moja. If we could get her to stop chewing her fingers, Moja would no doubt be a talkative companion; she had been signing since she was three months old and knew 150 signs. But we were also terrified. We didn't know Moja, nor she us. I had met her once for three days in 1977. How in the world would we handle a powerful chimpanzee who was, by most accounts, a neurotic tyrant?

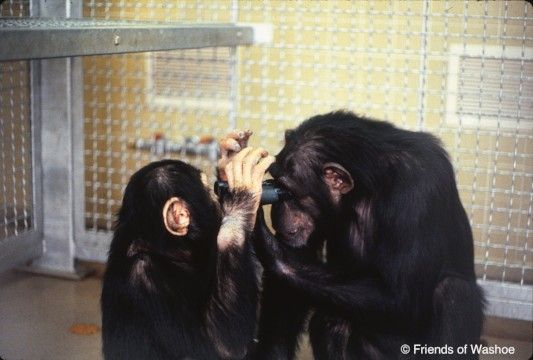

As it turned out, we didn't handle Moja; Washoe did. Moja had never been around a chimpanzee who was older, bigger, and stronger than she was. She had gotten used to bullying her younger brother and sister, Dar and Tatu, and assumed that humans would respond to her every scream and fret over her every wound. Now, 70-pound Moja found herself dealing with a 150-pound female who had an 18-month-old child to take care of. Washoe had no time for Moja's self-pity, and she put her in her place in a hurry. The day Moja met Washoe was the day she began growing up.

It was a rocky transition. Moja's separation from Allen and Trixie tore her apart. Washoe had landed on her feet in Oklahoma and had just kept right on going, but Moja was an emotional basket case. She wouldn't eat. She had constant diarrhea. She screamed all the time. She groomed her wounds until they bled. And when all else failed Moja would simply sign to us, HOME? GO HOME?, holding the sign in place for several seconds to stress her urgency.

It was heartbreaking to see Moja suffer and it was all too easy to cater to her every demand. When she demanded SANDWICH-peanut butter on white bread was all she ate-Debbi and I would fall over ourselves to make it. When she screamed we would anguish over why she was upset. When she chewed her fingers we begged her to stop.

Washoe dealt with Moja more straightforwardly. If Moja wouldn't stop screaming, Washoe would swat her on the head, as if to say, "I'll give you something to cry about," and Moja would instantly snap out of her crying jag. If Moja refused to eat her dinner, then Washoe would eat it for her. If Moja was trying to manipulate us by grooming her wounds, Washoe would turn it into a group activity by joining in the grooming. And if Moja was listless, Washoe would put Loulis on Moja's back and let her play "aunt" for a while. Loulis loved Moja, and his energy and affection seemed to bring her out of herself. Meanwhile, Moja was spending so much time worrying about what Washoe might do to her that she had little time to be morose.

It took a year for Moja's wounds to heal. When she did emerge from her depression she was a transformed individual. The biting, the bullying, and the self-mutilation had stopped. Moja would always be rather neurotic and eccentric, but she looked up to Washoe and she was truly devoted to little Loulis. Washoe had done something the Gardners and we could never do: she had taught Moja to be a social chimpanzee.

Fouts, R. & Mills, S. T. (1997). Next of Kin: My Conversations with Chimpanzees. New York: HarperCollins.